Edgar Schein, Sloan Professor of Management Emeritus at the MIT, describes three levels of organizational culture:

- artifacts, the visible sign: from dress code to how employees communicate

- espoused beliefs: the values by which business is conducted, it can be brought out by talking to people

- underlying assumptions, the invisible component: hard to describe, often unconscious, but often decisive for behavior

In this post, I'd like to describe some simple patterns of organizational change. They've been beneficial because they are not only limited to replacing our current artifacts with more advanced ones but also because all aspects of the organizational culture described by Schein are taken into consideration.

It Starts With What We Have

It is completely normal, in the practice of project management or project portfolio management, to start adopting simple tools, perhaps those we already have available for our individual productivity. There is nothing wrong with this and, up to a certain point, this approach works well.

As time goes by, we will end up perfecting this, maybe introducing a meaning of our own to some ways of representing information or gradually adding micro-detailed rules that increasingly help us in our work. The risk is that we may have created artifacts that only we are able to understand fully.

The question at this point becomes: how far can we go with this approach?

Put in this way, the answer seems very simple, perhaps even trivial. That's because each of us thinks we are absolutely able to understand how far we can go adopting our personal method. Unfortunately, however, in many cases, the strength of habits will end up being greater than our ability to be critical.

Yet it is not uncommon to find companies where to manage their initiatives, a collection of tools and artifacts are used with an evidently inadequate result in order to support the achievement of outcomes. I would like to tell you about some of the situations that my colleagues and I have encountered most frequently.

Most Common Patterns

First, I would like to mention the use of one or more spreadsheets, generally very, very large (it is necessary to scroll both vertically and horizontally to read them), whose ultimate purpose would be to monitor the status of all the work.

Inside it, we can find the work to be done together with options, the people to whom the work is assigned, requested delivery dates, the priority (on a scale of 1 to 10!), and numerous other columns that may relate to the involvement of an external partner, cost evaluation, or other verbose notes. Usually, this is not enough, so soon it becomes necessary to introduce more notes or comments to the cells.

Generally, after a certain period of time, only the author might be able to get useful information from this artifact.

Value-added documentation?

The second point I would like to address concerns the refinement of options. That's the phase where we have to decide if a project or an activity is worth doing and we have to proceed with the collection and evaluation of information for this purpose.

I believe many of us have been dealing with documents such as the "Business Case", the "Project Order", the "Project Charter", etc. I'm not saying that they are useless, but the point is that you may soon risk making them a ballast rather than a useful tool.

We need to ask ourselves a set of questions in order to assess the value of that documentation. For example, are we managing valuable documents or templates compiled in a non-participatory way? Have we established appropriate feedback loops to talk about these contents?

Do meetings enable conversations?

Here, I would like to touch on one more topic. In fact, it often happens that if we are too focused on our spreadsheets and documents, it is easy to forget that having well-designed meetings to manage our work is an integral part of the management system.

The point is that in many educational systems, designing and managing a meeting is not taught at all, and the generalized lack of this skill is evident. I'm sorry, but simple common sense is not enough to deal with such a complex topic.

Frequently, in many companies, there is a single kind of meeting, usually held on Monday.

Ordinarily, it is a generic type of meeting, without a specific agenda. It usually ends up condensing aspects that are too different from each other, such as generic communications, open problems with an immediate search for the solution, assignment of new activities to people, proposals for the introduction of new services, etc. It is clear to everyone that time will not be enough to dive deeper into all these topics but in the meantime, we are still talking about them.

Typically some people monopolize most of the time available, while the most introverted struggle to make their contribution. It is possible to observe certain disorientation: not everyone is clear about what they should do.

What Can We Do From Next Monday Instead?

There comes a time when we realize the limits of our current work management system and that our existing tools and artifacts, even if they have brought us this far, now contribute poorly to achieving the Outcome.

What can we do to improve things right away without the need to activate an expensive "Change Management" initiative with all of its risks of resistance? How can we activate what is undoubtedly a true cultural change?

The key is to introduce small sustainable changes in people's behaviors.

Proto-kanban: the foundation of a new work management system

The Kanban Method and the Kanban Maturity Model take this problem very seriously, which is brilliantly addressed by the principle of Change Management: "Start with what you are doing now!".

In practice, this means that we can begin our journey towards a more "fit for purpose" organization without worrying about all advanced agile and leadership practices. Instead, we can quickly design a simple "proto-kanban system" to represent what is currently running in our existing system.

The prefix "proto", which generically indicates both the first phase of a phenomenon or the development of an organism, in this case, refers to a partial version of a kanban system, where, for example, we don't worry too much about the management practice of the WIP limit.

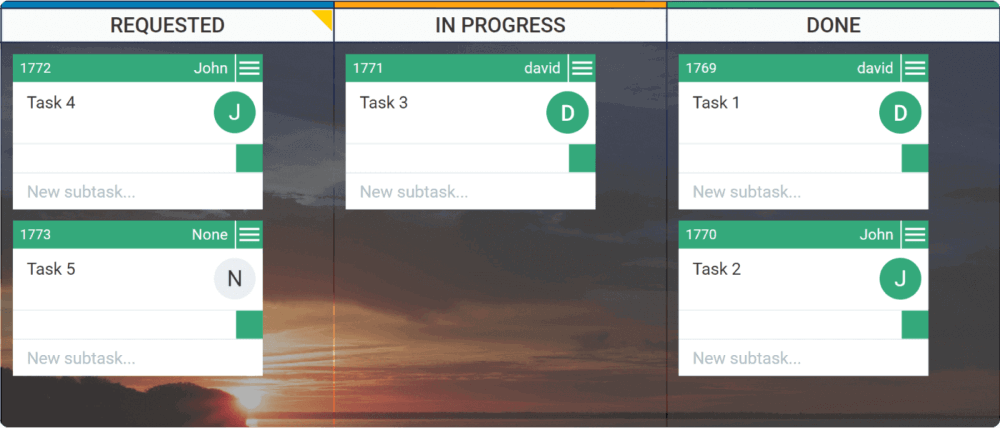

A simple Kanban board for visualizing existing work

A simple Kanban board for visualizing existing work

But let's be careful: there should be the intent to pursue the use of kanban systems and evolutionary change. A board on the wall with some cards, visualizing a workflow, would not be considered proto-kanban unless there is intent to use it as a way in an intentional pursuit of change. Without this, we will have just another artifact unrelated to people's values, assumptions, and behaviors.

Free from overload anxiety

That frees us from the anxiety of overload in the workflow and allows the team (or the project portfolio manager) to better understand how the provision of a service/product, or a program of many projects related to each other, actually occurs.

It is very interesting to observe how powerful the practice of visualization is, compared to the use of spreadsheets and how it is a stimulus to bring out valuable conversations among people involved in the workflow.

Usually, they begin to discuss issues regarding the elements of work in some progress states and some Policies, clarifying topics that have never been formally shared before. The team is ready to activate daily stand-up meetings in front of a Kanban board, their first feedback loop, in a spontaneous mode. Sometimes the spreadsheet continues to be updated in parallel, sometimes, it is quickly abandoned.

Analytics: fuel for conversations

In my opinion, one of the most important questions the "change agent" can ask the team right now is: where does our work begin and where does it end? There are now enough elements to answer this question easily.

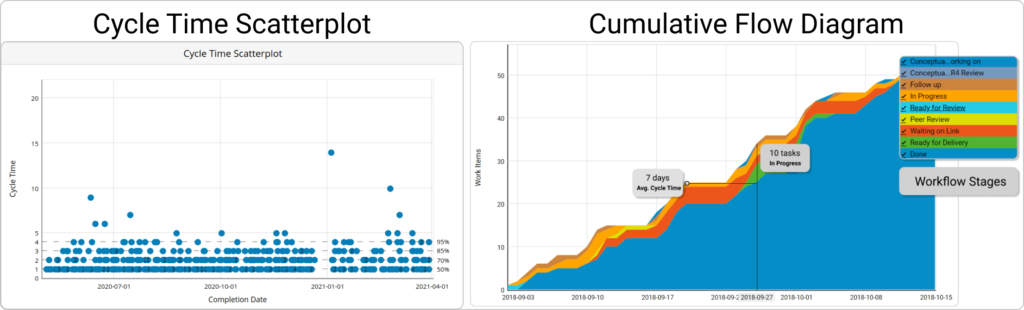

Knowing where our flow begins and where it ends, we can begin to consider the metrics for system improvement available in the "analytical module" of an advanced software solution.

People can observe the trend of metrics and charts like CFD, Cycle Time Scatterplot, Aging WIP chart, etc., and bring them back to specific situations in their work.

In these early stages of Kanban introduction, the leading indicators, such as Work in Progress and Work Item Age, are particularly useful, which continuously give us the pulse of our system and can be discussed daily at the Kanban meeting.

Good use of metrics enables the plan of small, sustainable changes for organizational improvement, whose effectiveness can be easily monitored.

Once those things are in place, the monster Spreadsheet and the Monday meeting to organize the world become a distant memory.

A different kind of documentation

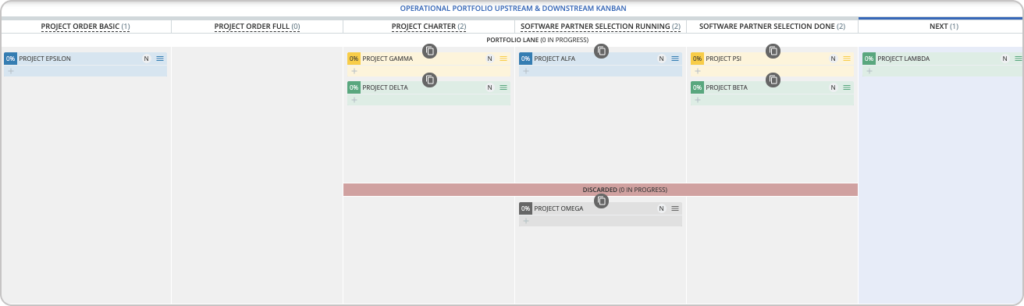

Regarding the topic of the Project Documents (like Business Case, Project Charter, etc.), it is natural to put them in correlation with the "Upstream" part of our flow: the activities that need to be completed to prepare the work for the delivery part of our system.

The advantage now is that, despite being imperfect, our work is observable thanks to the Kanban board and analytics, and we are familiar with these new tools. It is much easier to define the Upstream: the steps that, starting from ideas, come to define what is ready to start.

We no longer think in terms of documents to fill in but of activities to do and rules for making decisions regarding the progress of an idea towards the executive part of the system or its discarding. It is useful to have adequate Kanban apps that allow you to represent the upstream and downstream work separately or connected together, according to your needs.

Among the patterns observed in companies, we sometimes witness the birth of a new kind of documentation that is produced during each phase of the upstream. There, very interesting feedback loops begin to take shape, often involving more stakeholders and leading the organization toward greater maturity.

At this point, it is clear that even the Monday meeting can be turned into something different. Our system provides us with the elements to define iterations in our work and design feedback loops with very clear objectives. Without having to acquire particular facilitation skills, we can start creating very efficient meetings.

To sum up...

Distributing the various stages of introducing Kanban into the organization over a longer period of time is often the key to overcoming the fear of novelty and other causes that can trigger forms of passive-aggressive resistance to change.

People need to gradually develop a trust in the "Kanban System", to fearlessly abandon old artifacts and rituals. They need to change their behavior and follow a path that, as mapped by the Kanban Maturity Model, and according to Schein's definition of Organizational Culture, can take the organization very far.

David Bramini

Guest Author

David Bramini has over 30 years of experience in IT and consulting, co-founding companies across industries. With over 30 years in IT and consulting, David Bramini specializes in Corporate Strategy, Organizational Agility, and Project Portfolio Management. Co-author of Eco-OKR, he helps organizations connect strategy with execution and achieve sustainable growth through actionable strategies.